Orchard Point Oyster Co. SALT Feature

The following was originally written for ReadSalt, an online magazine about coastal life, and published in August, 2016. ReadSalt is no longer available and a version of my article has been republished here. Additional images from the project can be found on my website.

A Year with Orchard Point Oysters

Start-up Aquaculture on the Eastern Shores of Maryland

We had yet to finish loading the skiff and the sub-zero February temperatures were already approaching unbearable. “What am I doing out here?” I wondered as I clamored down the last wrung of a wooden stepladder, guessing the approximate distance between the damp, fiberglass hull of the SS Orchard Point (my name) and the layers of wool socks, work boots, gaiters and rubber deck boots that surrounded my feet.

We were heading out to the Orchard Point Oysters aquaculture lease, a five-acre block of water, four to eight feet in depth located near the mouth of the Chester River, and I considered how many times Orchard Point’s founder, Scott Budden, has asked himself the same question. Unlike me though, Budden doesn’t have much of a choice at this point. This is his livelihood.

Orchard Point Oysters has grown from concept to full-blown aquaculture farm in less than four years. The impetus of which was a change in state law that allowed for individuals and companies to lease portions of the Bay for private aquaculture ventures. Keen to relocate to his home waters of the Eastern Shore, Budden did his research and boldly extracted himself from the daily doldrums of a Washington, D.C. consultancy life to build an oyster farm from scratch. The first of its kind in the Chester River, Orchard Point Oysters serves not only as Budden’s full-time occupation but also a test case for the ecological and economic benefits of a reinvigorated oyster population throughout the Chesapeake Bay and its many estuaries.

The Farm

With two fully operational work boats, a full-time employee, numerous land-based storage facilities and a third of a million oysters approaching harvest, Budden is ready to plant his flag in the mid-Atlantic oyster scene.

This evolution did not come easily, with red tape, bouts of local resistance and a steep, time consuming learning curve. Through it all, Budden has nurtured a living and breathing nest egg that has the same boom or bust stability as any farmed product. A significant weather occurrence could wipe out a year’s worth of work. A shift in the market could send repercussions down his entire operation. Yet a successful harvest could provide the much needed windfall that powers the next year of his life.

Undaunted, Budden remains committed to his idea. My project started as a way to document the major milestones of his endeavor but has since evolved into a multi-faceted look into the everyday nuances of running his farm. I grew up on the water, too, and knew that the glamorous ideal of working on a boat during the warm, open embrace of summer months was a stark contrast to the harsh realities of running a year around off-shore operation.

Budden wouldn’t just be out on the water in the nice weather, when we all want to be, I understood, but would also be out fighting the elements in the bitter cold of winter. What did that look like? How does one equip themselves for those conditions and press on in the face of bitter climate adversity?

Which brings me back to that frigid February afternoon, decked out in more Carhartt gear than I have ever seen and lumbering around a cramped 21 foot Carolina Skiff, trying to put together a handful of pictures that properly convey these working conditions without getting in his way or plummeting into the river. Once aboard the skiff, we feed its two-stroke motor a mixture of oil and gas, crank it to life and set out through the cutting wind and over the river chop to check on the health and growth of a few hundred Orchard Point oysters.

The Mechanics

Safely anchored out at the lease, Budden demonstrates the working process of the winch-powered crane that takes up much of the real estate of his skiff. Once connected to a cage, the pull of a lever yanks a several hundred pound oyster cage clean off the river floor and plops them onto the boat deck for some attention. Oysters are cleaned, sorted by size and tumbled – roughed up in an effort to thicken their shells and deepen their cup – before they are put back into a cage and re-deposited onto the river bed. Each oyster receives this treatment about a dozen times throughout its life on the farm and the work goes on regardless of the weather, temperature or their owner’s disposition.

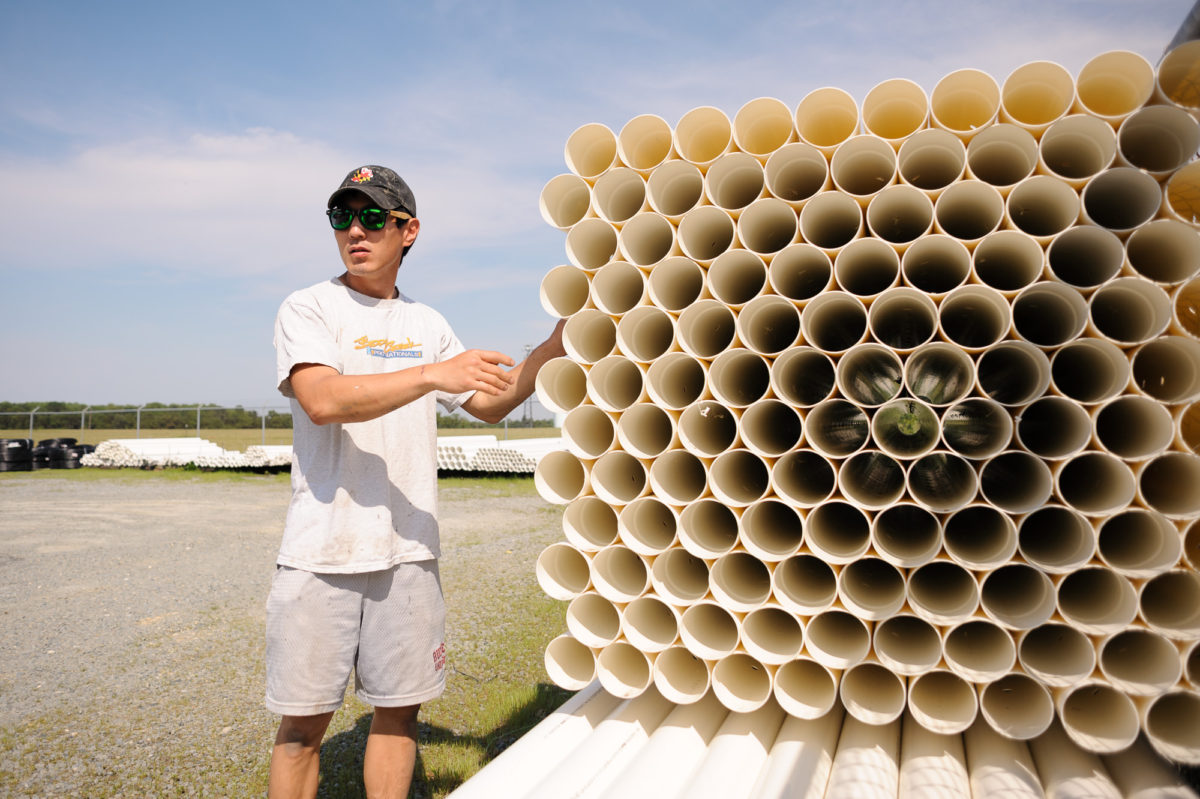

But the work doesn’t stop there. A small, upstart farming operation requires a considerable amount of construction, fabrication and at times, mechanical improvisation. Each of my visits to the home base of Orchard Point operations saw the construction of a tool, boat or facility that in some way supports the aquaculture process, showing that running a caged aquaculture farm is much more than raking bi-valves out of the water and throwing them into a cooler.

The Orchard Point work barge, a recently launched second vessel that is essential for the farming operation, started as two pontoon hulls and a metal frame. Budden built and fiberglassed its new deck by hand, along with its one of a kind PVC tumbler system for mechanically sorting, cleaning and roughing up his oysters that integrates with the gas powered hydraulics, pulley and washdown systems that make it all work. The new tumbler is staggering to observe in use, and nearly impossible to imagine building from scratch.

But that’s the life of a working farmer. Massive investments of time and energy, constant improvisation, slow progress and a new problem to solve or mountain to climb at every corner. The next big mountain is his first full-scale harvest. Much of his first crop, planted in June of 2015, is just about ready to hit market size. The crucial 2016 payload should help shore up his winter operations, pay off some start-up debt and establish Orchard Point within the distribution channels that will move his product from Chester River to restaurants throughout the region.

The skiff, crane, work barge and tumbler will all play a crucial role in making this harvest a success, but it’s the human element that puts the pieces in place.